The following article was originally posted on the Literary Ladies Guide website.

The Pink House by Nelia Gardner White is a 1950 novel that has the feel of a timeless classic. Yet like the rest of Gardner’s large body of work, it fell out of print and remained obscure and hard to find.

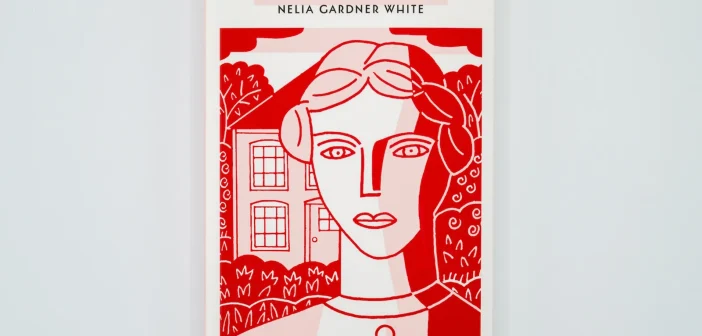

That is, until recently, when Independent press Quite Literally Books reissued it in a handsome new edition in 2025.

It’s surprising that a writer of her caliber would be so thoroughly forgotten. Her books were well reviewed and sold well. She was even a pioneer in the realm of what we now call biofiction: Daughter of Time (1942) is a novelization of the tragically brief and brilliant life of short story master Katherine Mansfield. It was warmly reviewed in the New York Times.

You have to do some persistent digging to find good copies Nelia Gardner White titles. Other novels include Woman at the Window, The Merry Month of May, The Thorn Tree, David Strange, Hathaway House, and others, including No Trumpet Before Him, which will be briefly discussed ahead.

The new edition of The Pink House is available from Quite Literally Books. See a roundup of QLB’s current titles here on Literary Ladies Guide.

The following appreciation of The Pink House is by Tyler Scott, a Literary Ladies Guide contributor:

The Pink House: An Appreciation

“Out of the fullness of my heart I write down this story of my life. The snow is falling, silently, gently, beyond the panes. Every branch is limned with snow.”

Thus opens the novel The Pink House (1950) by Nelia Gardner White. When I was about twelve years old, my mother handed me this novel and explained that it had been her favorite when she was my age. This was in the Adirondacks, where we had a summer place, and every year after that, I read the book during vacation. It became my favorite.

Nelia Gardner White (1894 – 1957) was an extremely popular and prolific writer. She was born in Andrews Settlement, Pennsylvania, one of five children. Though they weren’t wealthy (her father was a Methodist minister), hers was a happy childhood. As she grew up, she worked odd jobs so she could attend Syracuse University (1911 to 1913). She then attended Emma Willard Kindergarten School from 1913 to 1915 to become a teacher. She married a lawyer and had two children.

In her early career, White wrote children’s stories, articles on child-rearing, and young adult novels, mostly set in small towns. Over time, she began writing for adults. She wrote some twenty-five novels, all (save for the 2025 reissue of The Pink House) out of print, as well as countless stories and articlesfor the top magazines, reaching millions of readers. The magazines in which her work was published included Ladies Home Journal, Good Housekeeping, and McCall’s. A shorter version of The Pink House was serialized in The Woman’s Home Companion.

One of her career highlights was during World War II, when she was hired to write articles for the British Ministry of Information while living in England.

Now even more obscure than The Pink House,White’s 1948 novel, No Trumpet Before Him,, is the story of a Black man falsely accused of a crime and sentenced to death. It explores the power of a community coming together in the face of of racial injustice. No Trumpet Before Him was awarded the prestigious Westminster Fiction Prize, which came with a generous cash prize of $8,000 (equivalent to more than $100,000 today).

The Pink House is the story of Norah Holme. When the novel opens, seven-year-old Norah’s mother dies. Her father, who works overseas, doesn’t know what to do other than leave her with his sister and her family in their grand New England house, The Grange. Quiet and shy, Norah has scoliosis and uses a cane. Three of her cousins take an immediate dislike to her; only the oldest, Paul, shows her kindness. The spoiled cousins tease her, call her Toad, and won’t play with her.

Norah’s Aunt Rose is elegant, icy, and distant: the type of woman who has breakfast in bed and overspends. Her husband, Norah’s Uncle John, mostly keeps to himself and worries about money. Aunt Poll (John’s sister who lives with the family) takes Norah under her wing. Poll is stern and plain-speaking, but she ably educates Norah and teaches her to be tough, set goals, and live well despite her disability.

Norah’s growing strength and self-acceptance are qualities that may have appealed to post-war readers. It’s easy to see why the book made an impression on so many young women. The story is timeless and speaks to anyone who struggles with loneliness and lack of confidence while growing up.

White had a knack for building character and description. Her early works were sometimes criticized as sentimental women’s novels, but The Pink House defies this description. It’s a tableau of family life, with dynamics both good and bad. Secrets to be revealed keep the story moving forward, and, as the flyleaf of my original 1950 edition reads, “undercurrents of hate and frustration and mystery.”

I don’t want to divulge spoilers by give away the ending; however, in the end, good people prevail. With The Pink House, White wrote a novel in which even today, readers may find much to identify with, just as they did when it was originally published.

Excellent authors often leave us with wonderful quotes; this was one of my favorites from Nelia Gardner White on writing:

“One must have discipline, and discipline comes from failure, through writing thousands of words and using a few hundred of them, through filling the mind with great literature, through stretching the imagination to the utmost, through forgetting markets and concentrating on the immediate work. A surface cleverness is not enough.”