The following article was originally posted on the Literary Ladies Guide website.

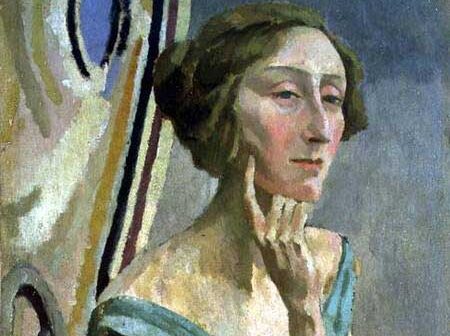

Dame Edith Sitwell (September 7, 1887 – December 9, 1964) was a British poet considered one of the first of the avant-garde movement. She had an enormous influence on literature and was also known for her eccentric demeanor, bon mots, and rather pronounced, if sarcastic, opinions.

As Elizabeth Bowen once said, she was “a high altar on the move.” Photo at right by Cecil Beaton.

An unhappy childhood

In many ways Edith was the quintessential poor little rich girl. Born in Scarborough, England, her aristocratic parents, Sir George Sitwell and his wife, Lady Ida Denison, lived in the family home in Derbyshire, Renishaw. The family fortune came from land and ironmaking.

Unhappily for their young daughter, the Sitwells were cold and distant parents; some even guessed that Lady Ida, a volatile woman, may not have wanted her. It didn’t help that the pale and gangly child had a beaked nose and crooked back, her parents therefore keeping her in braces for most of her early years.

Edith must have been a precocious and bright child: At four years of age, she told her parents she wanted to be a genius when she grew up. She never did forgive her mother for her terrible childhood, and later, didn’t bother to attend her funeral.

She was very close to her two brothers, Osbert Sitwell and Sacheverell Sitwell, both of whom also became famous writers. For many years her closest companion, with whom she later lived in London and Paris, was her governess Helen Rootham, herself a poet.

First publications

In 1915 Edith published her first poetry collection Mother and Other Poems. A year later she and her brothers were putting together the poetry anthology Wheels, a showcase for fellow modernist poets, which had six issues and was a reaction to the sentimentality of the Georgian movement. The Sitwell siblings were now known as “the alternative Bloomsbury” and running in the same circles as William Butler Yeats and T. S. Eliot.

What made Edith’s poetry most interesting was that she took everyday topics and gave them a modern slant; she was a matador of words. One critic said she “tilted Romanticism on its head.”Her themes were life, death, and the human condition.

Her work can be divided into two periods, the early pieces were often nonsensical and playful, the later more serious. The poet Charles Baudelaire was a great influence Her poems had a certain rhythm, and many were set to music by composers such as William Walton and Benjamin Britten for performances.

Thoughts on poetry and major achievements

Edith Sitwell explained her attitude towards sound in poetry in her autobiography, Taken Care Of (1965):

“Rhythm is one of the principal translators between dream and reality. Rhythm might be described as, to the world of sound, what light is to the world of sight. It shapes and gives new meaning. Rhythm was described by Schopenhauer as melody deprived of its pitch.”

Her masterpiece is considered the poem Still Falls the Rain which was written during the London Blitz of World War II. It intertwines the suffering of the people with the suffering of Christ and ends on an element of hope. (.)

The body of work Edith left behind was considerable: Twenty-one poetry collections; books on Queen Victoria, Elizabeth I, and Alexander Pope; a novel; an autobiography; and a book on English eccentrics, among others. She was made a Dame of the British Empire in 1954.

Richard Greene, well-known poet, biographer, and a professor of literature and creative writing wrote at the University of Toronto wrote two books on Edith Sitwell which are highly respected: Edith Sitwell: Avant Garde Poet, English Genius and Selected Letters of Edith Sitwell (editor).

When I spoke to him, he mentioned he believes that Edith Sitwell’s work was often criticized because she was a “soft target” and was writing in the days you could “dismiss a woman poet.” After all, no one was going to take on titans like William Butler Yeats or T.S. Eliot.

Eccentricities and idiosyncrasies

It’s impossible to write about Dame Edith without mentioning her idiosyncrasies. Her dress was flamboyant and somewhat Elizabethan: brocaded gowns; clunky jewelry (now displayed in The Victoria and Albert Museum); velvet turbans; and capes. With her chalky face, hawk nose, and thinly lined eyebrows, she cut quite a figure and proudly so.

In her words, “I am not eccentric. It’s just that I am more alive than most people. I am an unpopular electric eel set in a pond of goldfish.”

She never married and seemed to have a penchant for unavailable men who were mostly homosexual, including the poet Siegfried Sassoon, and the painter Pavel Tchelitchew.

To her credit, she championed Dylan Thomas and Denton Welch when they were young writers

With her flair for drama, she was also infamous for the feuds she had with luminaries like Robert Graves, D.H. Lawrence, and Wyndham Lewis.

Noel Coward once wrote a sketch called The Swiss Family Whittlebot which made fun of the Sitwell siblings and caused hostilities for years. Perhaps this was why she developed such a rapier wit: It was to protect herself, or as Prof. Greene once explained, “a way of keeping human suffering at bay.”

After Dame Edith’s death in 1964, times and literary tastes changed, and she began to slip into oblivion. Thankfully, Professor Greene said her reputation is starting to recover: her work is showing up in more anthologies and she is “spoken of more seriously” these days.

Perhaps Katherine Anne Porter said it best when describing Dame Edith’s work as “the true flowering branch springing fresh from the old, unkillable roots of English poetry, with the range, variety, depth, fearlessness, the passion and elegance of great art.”

“The Innocent Spring” (1924) is one of Dame Edith’s loveliest poems:

The Innocent Spring

In the great gardens, after bright spring rain,

We find sweet innocence come once again,

White periwinkles, little pensionnaires

With muslin gowns and shy and candid airs,

That under saint-blue skies, with gold stars sown,

Hide their sweet innocence by spring winds blown,

From zephyr libertines that like Richelieu

And d’Orsay their gold-spangled kisses blew;

And lilies of the valley whose buds blonde and tight

Seem curls of little school-children that light

The priests’ procession, when on some saint’s day

Along the country paths they make their way;

Forget-me-nots, whose eyes of childish blue,

Gold-starred like heaven, speak of love still true;

And all the flowers that we call ‘dear heart’,

Who say their prayers, like children, then depart

Into the dark. Amid the dew’s bright beams

The summers airs, like Weber waltzes, fall

Round the first rose, who, flushed with her youth, seems

Like a young Princess dressed for her first ball.

Who knows what beauty ripens from dark mould

After the sad wind and winter’s cold?

But a small wind sighed, colder than the rose,

Blooming in desolation, ‘No one knows.’

Further reading and sources

- Greene, Richard, author of Edith Sitwell: Avant Garde Poet, English Genius. Great Britain: Virago, 2011.

Personal interview, June 25, 2024. - Greene, Richard, ed. Selected Letters of Edith Sitwell. Great Britain: Virago, 1997.

- Poetry Foundation, Edith Sitwell.

- Edith Sitwell, British Poet, Encyclopedia Britannica, 1998-2024 (updates).

- Cooke, Rachel. Edith Sitwell: Avant Garde Poet, English Genius by Richard Greene – review. The Guardian. 2011.

- Staff, Harriet. After 30 Years, a new Edith Sitwell Biography– review of Richard Greene’s

Edith Sitwell: Avant Garde Poet, English Genius. Poetry Foundation website, 2011. - Meyers, Jeffrey. Review of Edith Sitwell: Avant-Garde Poet, English Genius by Richard Green,

The Globe and Mail, May. 2011.

Contributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life.