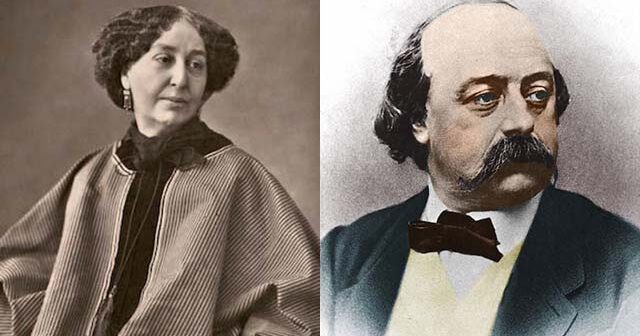

The friendship and correspondence of George Sand (1804 – 1876) and Gustave Flaubert (1821 – 1880) form a fascinating and valuable chapter in literary history.

Their letters are vignettes of the tumultuous time of the 1848 revolution, the Franco-Prussian War, and the fall of the Paris Commune. They’re also discussions of the challenges of writing, the world of theater and politics, and the whims of family and friends.

In Flaubert-Sand, The Correspondence (1993), the late translators and researchers Francis Steegmuller and Barbara Bray opened this 19th-century world to readers. Presenting four hundred letters from earlier books, libraries, and private collections, this volume has extensive footnotes, excerpts from Sand’s diaries, and chronologies for context.

Like many friendships, theirs started by chance. The two met causally in Paris at the theater and Flaubert invited Sand to the famous dinners at Magny (a small restaurant in the Left Bank of Paris) for writers organized by the publishers Goncourt and Sainte-Beuve. Sand would be the only woman attending. By then, she was a well-known novelist and playwright.

Coming to Flaubert’s defense

Sand had watched Flaubert’s popularity ascend, but it was the controversy that arose after the publication of Madame Bovary that raised her ire.

When the novel was published in 1857, the government charged the author and publisher with immorality because the work was “grossly offending against public morality, religion, and decency.” The trial, which lasted a year, ended in acquittal. Sand felt her colleague had been dealt with unfairly.

When Flaubert’s next novel, Salammbo, was published in 1862, the reviews were lukewarm. He sent Sand a copy and she wrote an enthusiastic article for the Parisian newspaper La Presse. In turn, he told a friend of her kindness and probably wrote her a letter of thanks. Although it doesn’t survive, Sand’s response does:

January 1863

Mon cher frère,

Don’t thank me for having done my duty. When the critics do theirs I’ll be quiet: I’d rather create than judge. But all I’d read about Salammbo before I read Salammbo itself was unfair or inadequate, and I’d have thought it either cowardly or lazy — they’re much the same thing — to be silent. I don’t mind adding your enemies to my own. A few more one way or the other. . .”

What followed was a thirteen-year epistolary friendship not only benefitting the authors, but also future readers, writers, and historians. It’s our fortune that so many of these letters have survived.

One of the sources for the Steegmuller book was The Correspondence of Gustave Flaubert – George Sand, edited by Alphonse Jacobs (Flammarion, 1981). He wrote in the preface:

“It has often been said that this is the finest correspondence of the past century, perhaps the finest of all time. Everyone has emphasized its historical importance, its great place in the literary, philosophical and political ideas of the nineteenth century. We are told all writers and students should be familiar with it as part of their education; and that today’s generations could profit from the moral lessons it provides.”

Gustave Flaubert — melancholic and ill

Flaubert and Sand were seventeen years apart – he was the same age as her son Maurice – and they couldn’t have been more different in temperament and style.

Flaubert was prone to melancholy and complaining; ill health (he had syphilis and probably epilepsy). He hated exercise and was a curmudgeon who didn’t suffer fools. He looked down on the bourgeoisie (though he was the son of a doctor) and their social-climbing, materialistic ways. He lived in a cold and drafty home called Croisset, south of Rouen on the Seine River, where he resided with his widowed mother (who paid most of the bills) and an orphaned niece.

Flaubert’s father had wanted him to study law, but as a young man, he had other ideas. He traveled around the Middle East, and when he returned, he began to pursue literature. For ten years, he wrote fiction without getting published and his family worried about his ability to make a living.

There had been lovers, particularly the writer Louise Colet, with whom he had a torrid affair that ended badly. She wanted to marry and have a child; he didn’t. Flaubert was no a stranger to brothels.

George Sand — a hardy sensualist

Sand, born Amantine Lucile Aurore Dupin, was the daughter of an officer in Napoleon’s Italian army and a peasant woman. Through various relatives, she was related to royals and when her parents passed away, her grandmother raised her on her estate, called Nohant, in the old Berry province of France.

Growing up at Nohant gave Sand a true love for country life and nature. At age thirteen, she was sent to a convent in Paris for two years; her grandmother then decided she didn’t want her granddaughter to become a nun. Upon returning home, she continued her schooling with a tutor who had formerly been an abbé.

Soon after her grandmother’s death, she married the son of a baron who fathered her two children. He also had a taste for maids and drink, and the couple separated permanently.

In Sand’s Paris years, she embraced the bohemian life, wearing trousers, smoking cigars, and writing articles promoting her youthful views on socialism; she eventually co-authored a novel and then wrote Indiana (1832) on her own.

Sand’s love life was colorful as well: Merimee, Musset, Chopin. . . By the time she and Flaubert became friends, she was happily ensconced at Nohant with her son and his family, at the beckon of beautiful gardens.

Very different kinds of writers

As writers, Flaubert and Sand were also a study in contrasts. Flaubert would often take a week to write a page. Andre Maurois, in his biography Lelia, The Life of George Sand, (1953), wrote:

“Flaubert would lie awake all night sweating over a single word. Sand would knock off thirty pages in the same period, and start on a new novel a minute after finishing the one she had been working on.”

Flaubert wrote for perfection, the ethereal world of literature, and not autobiographically. Sand wrote for money, often using her home as a setting.

Over the course of their lives, Sand would publish seventy-two novels and thirteen plays. Flaubert would publish thirteen novels as well as short stories. His literary realism had an enormous influence on the likes of Maupassant, Zola and set the path for modern fiction.

Devoted correspondents with a deep friendship

In their letters, Flaubert would address Sand as “Dear Master “or “Dearly Beloved Master.” She dubbed him “My Monk” or “My Troubadour.”

In 1866 Flaubert wrote to Sand after her visit to Croisset:

Everybody here is devoted to you. Under what star were you born thus to combine in your person so many rare and diverse qualities? I do not know how to describe my feelings for you. All I do know is that you have awoken in me an affection of a very special kind, such as I have never, till now, felt for anyone. We get on well, don’t we? It was so nice seeing you . . . I too, wonder why I am so fond of you? Is it because you are a great man or a charming creature? I really cannot say . . .

And her response to him, several months later in 1867:

You have not, like me, an itching foot ever eager to be off. You live in your dressing-gown — the great enemy of freedom and the active life …

And a few weeks later:

I have never ceased to wonder at the way you torment yourself over your writing. Is it just fastidiousness on your part? There is so little to show for it … As to style, I certainly do not worry myself, as you do, over that. The wind bloweth as it listeth through my old harp.

‘My’ style has its ups and its downs, its sounding harmonies, and its failures. I do not, fundamentally, much mind, so long as the ‘emotion’ comes through. But it is no use my trying to screw it out of myself. It is the ‘other’ who sings through me, well or badly, as the case may be. When I begin to think of all that, I get frightened, and tell myself that I count for nothing, for nothing at all. . .

Let the wind blow a little through ‘your’ strings. I think you fret about it all much more than you should, and that you ought to let the ‘other’ have his say more often. Everything would work out all right, and it would be a great deal less exhausting for you …

Sand played the idealistic mother hen to Flaubert’s angry suffering soul. They tried to change each other’s opinions, and though neither ever truly succeeded, the discussions were always lively. Sand lectured Flaubert on his unhealthy attitude and lifestyle, even once suggesting he marry.

Flaubert, the good friend and errant “son” would take this in stride and defend himself. Even so, these weren’t mere diatribes. The two talents wrote with style, passion, empathy, and pride; the leitmotif of their correspondence was respect and love, even extending to family.

George Sand on the problem of writing in a letter from December 1875:

… you’ll go in for desolation, I’ll wager, while I go in for consolation. I don’t know what our destinies stem from. You watch them go by, analyze them, but abstain, literarily, from judging them. You confine yourself to describing them, carefully and systematically concealing your own feelings. And yet those feelings can be seen through what you write, with the result that you make your readers sadder than they were before.

I’d like to make them less unhappy. I can’t forget that my own conquest of despair was due to my will, and to a new way of seeing things that is completely opposite to the view I once had.

I know you disapprove of personal attitudes entering into literature. But are you right? Isn’t your stand due to lack of conviction rather than aesthetic principle? One can’t have a philosophy in one’s soul without its showing through …

Flaubert responded on New Year’s Day, a few weeks later:

I don’t ‘go in for desolation’ wantonly: please believe me! But I can’t change my eyes! As for my ‘lack of conviction’, alas! I’m only too full of convictions. I’m constantly bursting with suppressed anger and indignation.

But my ideal of Art demands that the artist reveal none of this, and that he appear in his work no more than God in nature. The man is nothing, the work is everything! This discipline, which may be based on a false premise, is not easy to observe. And for me, at least, it’s kind of a perpetual sacrifice that I make to good taste.

Some of the letters I enjoyed most included descriptions of visits to one another’s homes. The get-togethers at Croisset sound like pajama parties: the authors would stay up all night, smoking, reading their works to one another, and raiding the kitchen.

In the daytime, they’d go on long walks (despite Flaubert’ physical laziness) and visit the sites in Rouen. Flaubert’s mother cherished Sand. His visits to Nohant were a swirl of parties, puppet shows, Sand’s beloved grandchildren afoot, other visitors like Turgenev, and walks in the garden.

Conclusion

As I neared the end of the Steegmuller book, I dreaded the end of this historic friendship. George Sand died at Nohant in June 1876 at the age of seventy-two, after a brave, painful battle with stomach cancer. She was buried in the drizzling rain with Flaubert at her graveside. Part of the eulogy was a poem written by Victor Hugo. Flaubert later wrote to her son Maurice, “It seemed to me that I was burying my mother a second time.”

At the time of Sand’s death, he was halfway through a story called “A Simple Heart,” which he was composing in tribute to her.

The subsequent years weren’t kind to Flaubert. His mother died, and his niece’s speculating husband racked up enormous debt so he gave up his inheritance to help her. Lonely, sad, and struggling with a myriad of health and money problems, Flaubert died of a stroke in May 1880, leaving behind the unfinished novel Bouvard and Pecuchet. He is buried with his family in a graveyard in Rouen. He was just fifty-nine years old.

Contributed by Tyler Scott, who has been writing essays and articles since the early 1980s for various magazines and newspapers. In 2014 she published her novel The Excellent Advice of a Few Famous Painters. She lives in Blackstone, Virginia where she and her husband renovated a Queen Anne Revival house and enjoy small town life.

Image of George Sand copyright has expired and is in the public domain. The image of Gustave Flaubert is from Wikipedia, and is in the public domain.