Virginia folk artist Eldridge Bagley tells the stories of everyday life in a small town—on canvas.

On a golden November day, I drove through the farmland of Lunenburg County in Southside Virginia to meet the painter, Eldridge Bagley. He is one of few celebrities who have lived here (our other claims to fame are Roy Clarke, who was born in Meherrin, and Bea Arthur attended Blackstone College for Girls). I had read about Mr. Bagley in our local newspaper so I called and asked for an interview, mentioning the name of my husband’s cousin whom everyone knows so he wouldn’t think I was a complete stranger.

At 75-years-old, Bagley still lives on his grandparents’ tobacco farm outside of Victoria, where he grew up and tilled the land. Unlike his siblings, Bagley was never interested in attending college and as he explained in a 1996 interview, “I’ve lived here. I’ve pulled tobacco. I’ve plowed behind a mule. I’ve brought in wood. I’ve shucked corn. I’ve helped with stew—I’ve done almost everything that can be done around here. I know what it’s like and I’ve worked with the people who do it.”

This is why his paintings so beautifully capture the farmland and small towns from memory: a tapestry of his life.

To this day, Bagley remembers the seminal moment when he was inspired to paint. In 1973, after a stint in the National Guard, he read an article about Grandma Moses, who didn’t start painting until her ’70s. Like him, she had no formal training. Her style, her innate talent—the fact she painted until her dying day at 101-years-old—was the push he needed. He bought a paint-by-number set at a dime store and, without going by the design, painted a picture of a covered bridge on the back panel; by then, his parents had a small antique store on their farm, and he displayed the picture and asked $3.50. All these decades later, he still laughs because no one bought the scene, which he still owns.

As for most artists, one thing led to another. Bagley started showing his work at art festivals, banks, libraries and doing commissioned works of people’s houses. Eventually, he grew bored with this—he wanted more creativity—so he went to Richmond and introduced himself to a gallery owner who mounted a show. The newspaper reviews were glowing, word spread, and he sold all the paintings. Bagley stayed loyal to the Richmond galleries and remembered feeling shocked when he realized he could make a living as a painter.

During his career, he has had several successful museum shows, and his paintings are part of permanent collections. The Folk Art Society of America named him “Artist of the Year” in 2011. Nowadays, paintings can fetch a few thousand dollars each, although smaller works are less expensive.

Eldridge Bagley has been called a folk artist, a term that puzzles him, although understandably; many artists don’t like to be pigeonholed. Folk art is sometimes used to describe painters who tend to be self-taught. Critics have used adjectives like “naïve” or “vernacular,” suggesting the style is unsophisticated. Gerard C. Wertkin, the former director of the Museum of American Folk Art in New York, once explained that defining Bagley’s works as simple folk art was missing the mark, using words like “multi-textured” and “highly original,” more aligned with the regional painters of the midcentury, showing ordinary people going about their business in the heartland.

During the early years, Bagley painted on Masonite, a type of hardboard, and he switched to canvas in the mid-1980s, mostly using cotton and sometimes linen. He begins with a pencil sketch for space and perspective, rarely using photographs. Some of his work is autobiographical, though most comes from the shadows of a vivid imagination. The painters he most admires are Thomas Hart Benton and George Henry Durrie, whose work was reproduced by Currier & Ives.

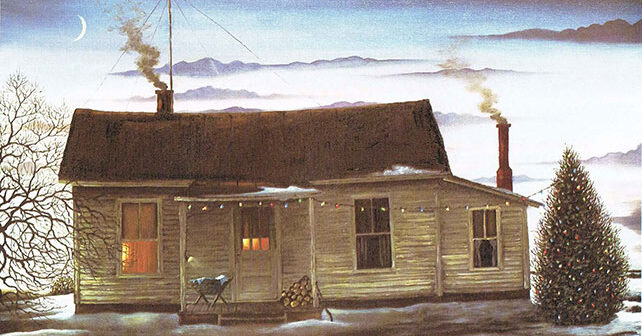

The paintings I saw at Bagley’s farm were softly lit and very calming. Many tell a story—he has never been a nostalgist per se—and even when there is an element of sadness, he offers hope. Later, when I looked at Son of the Soil, Soul of an Artist, a coffee table book he’d given me with copies of his work and biography, I was stunned at the depth in his art. In “Stand by Me,” an elderly lady gazes at the ruins of her house; only the chimneys are left. She is surrounded by friends and family who are consoling her. Yes, there has been a devastating fire, but those in the painting are there to help. Bagley depicts the possibility of rejuvenation.

On the other hand, I felt cheery when I looked at “Gathering Pears,” where a family gathers fruit on their farm, old black truck loaded up, sheep grazing in the background, Mama in her apron, Daddy on the ladder. A happy family on a sunny day.

In the painting “Two Roads,” Bagley captures the urban vs. the rural: an old tobacco barn, cows and a tractor in the foreground, a highway and McDonald’s sign way back behind the trees. Or there’s “The Watch,” where bulldozers are clearing a field near a farmhouse alongside a sign saying “Future Home of Walmart Supercenter.” Three men sit in a nearby pickup marked Seay’s Hardware.

Bagley is your quintessential Southern gentleman with an air of grace, patience and a sense of humor. Today, he lives on his farm with his wife Beth, a retired nurse, and surrounded by family; his son and daughter-in-law had brought home their newborn the week I visited, Bagley’s first grandchild. Life in the country has come full circle.

“At the core of my paintings, I wanted to capture a way of life I have experienced firsthand and wanted to share,” says Bagley. “I hope my work has helped preserve an up-close look at a way of life that has in many ways almost vanished. “

No doubt Grandma Moses would have been pleased.

You can also read the full article by Tyler on the Deep South Magazine website.

Featured painting: 1990 Approaching Christmas 18×24 linen.

Find Eldridge Bagley Art on Facebook. Image used with permission by Eldridge Bagley

Tyler Scott is a writer who lives in Blackstone, Virginia.